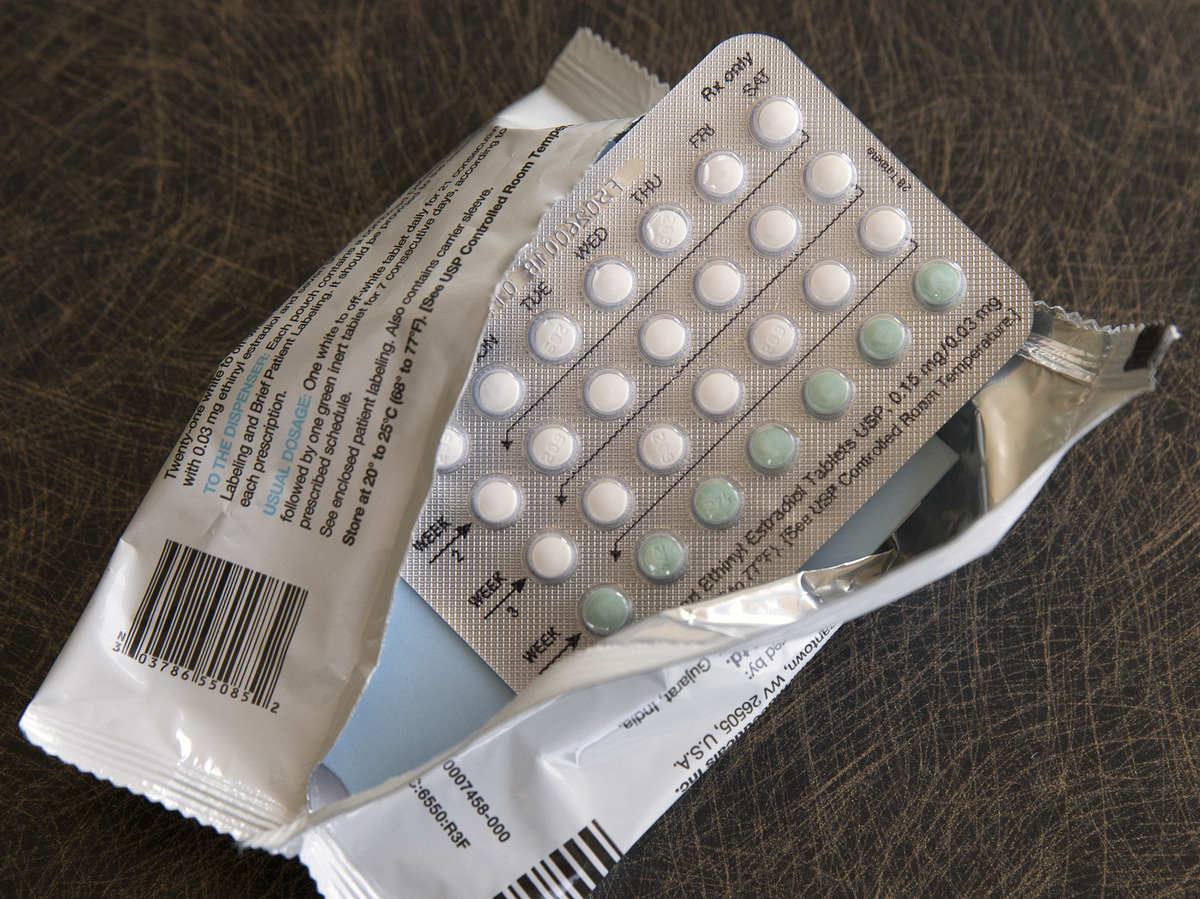

The Catholic healthcare system can limit access to contraception.

Photo by Rich Pedroncelli/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Photo by Rich Pedroncelli/AP

The Catholic healthcare system can limit access to contraception.

Photo by Rich Pedroncelli/AP

Students were shocked when they returned to the campus of Oberlin College, Ohio last week. Local news media reported that campus student health services would severely limit who can receive contraceptive prescriptions. Administered only to treat health problems, not to prevent pregnancy, emergency contraception will only be available to victims of sexual assault.

It turns out that the university had outsourced student health services to a Catholic health agency, and like other Catholic health agencies, it follows a religious directive prohibiting contraception to prevent pregnancy. Care that affirms is also prohibited.

“I characterize the student reaction as anger,” says Remsen Welsh, a fourth-year student at Oberlin and co-director of the campus’s student-run sexual information center. “A lot of people in my circle were sending [the news story] what happened? “

While the university was quick to come up with new plans to provide reproductive health services to students on campus, the incident in Oberlin was dictated by the prevalence of Catholic health care in the United States and by the rules these institutions follow. indicates that access to contraception may be limited.

Access to contraception is also becoming more difficult as many states, including Ohio, have now taken steps to restrict or outright ban abortion.

Religious Restrictions Affect Many Medical Practices

The ethical and religious directives that guide the Catholic health care system, issued by the Catholic Bishops’ Council of America, “ban a wide range of reproductive medicines,” including contraceptives, IUDs, tubal ligation and vasectomy, said the professor. said Dr. Debra Stulberg of Doctor of Family Medicine at the University of Chicago who has studied how these instructions work in healthcare.

Catholic hospitals have long been a pillar of American medicine. And more recently, the Directive has been applied to a wide range of settings where people seek reproductive health care. This includes emergency care centers, clinics, and ambulatory surgery centers. These have been acquired or merged by the Catholic medical system.

They are also applicable when Catholic health institutions are hired to manage the medical services of other institutions. This is what happened in Oberlin.

According to a 2020 report, four of the ten largest health systems in the country are Catholic. In some counties they dominate the market. In 52 communities, only a Catholic hospital is within a 45-minute drive, according to the report.

“After all the consolidation, this is rocking. About 40% of women of reproductive age live in areas where Catholic hospitals have a high or dominant market share.” Pittsburgh, looking at data in 2020. .

“Not transparent at all”

Patients are often unaware that these restrictions can affect the treatments they receive, says Lois Uttley, senior counsel at the health advocacy group Community Catalyst. They may not be aware that their hospitals and clinics are affiliated with Catholicism. For example, Common Spirit Health, one of the largest medical systems in the United States, is Catholic, but you can’t tell from the name. Utley also said that Catholic medical institutions typically do not publish these policies.

“They aren’t open or transparent about it,” says Utley. “I think it’s fair to warn patients in advance about what they can and can’t get at their local clinic, urgent care center or hospital.”

In a campus bulletin published Tuesday, Oberlin’s president, Carmen Twiley-Amber, said these restrictions were imposed on Bonn, the large Catholic health system whose subsidiary was hired to run the university’s health services. Bon Secours told the local Chronicle-Telegram that contraception for medical reasons, an exception allowed under religious dictates, was said to have only recently become known to Oberlin. It said it would only provide prescriptions.

Oberlin College president Carmen Twillie Ambar said Oberlin recently learned that contraceptive restrictions are enforced by the Catholic health system, which has hired a subsidiary to run the college’s medical services. At the beginning of , she participated in meetings with US Vice President Kamala Harris and presidents of other colleges and universities on access to reproductive health care.

Samuel Colm/Bloomberg via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Samuel Colm/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Oberlin College president Carmen Twillie Ambar said Oberlin recently learned that contraceptive restrictions are enforced by the Catholic health system, which has hired a subsidiary to run the college’s medical services. At the beginning of , she participated in meetings with US Vice President Kamala Harris and presidents of other colleges and universities on access to reproductive health care.

Samuel Colm/Bloomberg via Getty Images

If only workarounds

In fact, many physicians working for Catholic-owned or affiliated health care providers routinely rely on “medical condition” exceptions as a way to circumvent religious restrictions on contraception. , found in Stulberg’s study.

For example, a hormonal IUD can be used to control heavy menstrual bleeding, so doctors often say they offer an IUD to treat this condition, even if the actual purpose is contraception.

Alternatively, a doctor not authorized to perform a tubal ligation may remove the tube entirely instead. Suffice to say, it’s to lower a patient’s risk of ovarian cancer.Corinne McLeod, Ph.D., her OB/GYN at Albany Medical Center, said that when she worked at a Catholic hospital in Albany, N.Y. workaround was fairly common.

“It was basically wink, wink, nudge, nudge,” McLeod said, adding, “Everyone knew what was going on. That was their way of getting around. [restrictions]One of the problems with relying on such loopholes, she said, is that if religious officials at the institution find out about it, they may crack down.

In other cases, a workaround might involve creating a separate funded and operated department within a Catholic hospital or clinic to provide all kinds of reproductive health services.

That’s what really happened at Oberlin College. The university said it partnered with a local family planning clinic to offer these services three days a week on campus and provide students with transportation to the clinic on other days. However, Catholic healthcare providers will continue to provide other healthcare services on campus.

Tiffany Yuen, a senior at Oberlin College, who runs the Sexual Information Center with Wales, said the solution was “a starting point, but not enough.” In the past, about 40 percent of visits to the student health center were sexual, according to her Aimee Holmes, a certified nurse midwife who worked for many years as a women’s health specialist at Oberlin until a subsidiary of Bon Secours took over. was related to health.

Students at Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio, were outraged to hear that the Student Health Center would limit who could use contraception after the Catholic health system took over student health services.

Tony Dejak/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Tony Dejak/AP

Students at Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio, were outraged to hear that the Student Health Center would limit who could use contraception after the Catholic health system took over student health services.

Tony Dejak/AP

“Sometimes women really have no other choice.”

Studies show that even with workarounds, Catholic directives can limit women’s contraceptive options. For example, in one study, it was very easy for a patient to make an appointment for hormonal contraception at a clinic owned by a Catholic hospital, but if she needed one of the most effective forms of her copper IUD, she made an appointment. seldom took. Long-acting reversible contraception.

I myself faced these limitations eight years ago when I gave birth to my second child. When I asked my doctor for a tubal ligation when I was on the delivery bed, she said that because I was in a Catholic hospital, I couldn’t perform the surgery. Studies have found that women who give birth in Catholic hospitals are half as likely to have tubal ligation or removal than women who give birth in other types of hospitals.

According to a study conducted by Stulberg, many people are unaware that their healthcare providers are governed by these rules, which limits their choices. “And most of the people who refused reproductive health realized they couldn’t get what they wanted until they got there, or later,” she says.

In some cases, patients may be able to go to another provider to get the contraceptive they need, but this is not always the case. Sometimes not,” Stulberg says. “This hospital or this system is the only provider in town.”

She says a patient’s options may also be limited by health insurance and whether the provider covered by the plan has a religious affiliation.

Some experts say these restrictions can often disproportionately affect low-income patients. She says that when she worked as a resident at a hospital, treating many of the low-income people, patients who came in for an IUD appointment were told they had to go. Go to another non-Catholic clinic to insert the device.

“Any time you need to add another step to receive care or contraceptive care, it’s like another point where an unintended pregnancy can occur,” says Dara.

In fact, Catholic mandates can limit access to contraception even after medical facilities are no longer Catholic, says Elizabeth Sepper, a religious liberty and health law expert at the University of Texas at Austin. says. “There are many examples of the Catholic medical system buying a hospital, holding it for several years, and then selling it,” she says. We promise to continue the restrictions.”

Advocates of reproductive rights would like to see legislation mandating greater transparency about the health services the hospital system provides and does not provide. New York legislators introduced such a law.

“As you know, I’m not against Catholic medicine, but I think patients need to know the types of services available to them.” Yarensky says.