“I didn’t want to make up for the price increase. I wanted the customer to understand,” O’Brien said.

She was afraid of customer backlash, but the feedback was overwhelmingly positive.

“We thanked our guests over and over again,” he added, adding that he had never experienced a pushback incident at the Tycoon de Loga Club.

Vizethann estimated that 90% of Buttermilk Kitchen’s customers were “very kind and positive” about this decision, but some wonder why she simply doesn’t raise the price.

“I don’t want to price myself from the market,” she said.

In addition, she said that working on service charges as advertising information rather than folding costs into prices gives them flexibility and helps with accounting. “If you have a guest who is eager to not pay, just remove it,” said Vizethann, who removed the fee from the customer’s invoice twice after implementing the new policy in the fall. rice field. “As separate subscription information, you can see exactly what is contributing to that contribution.”

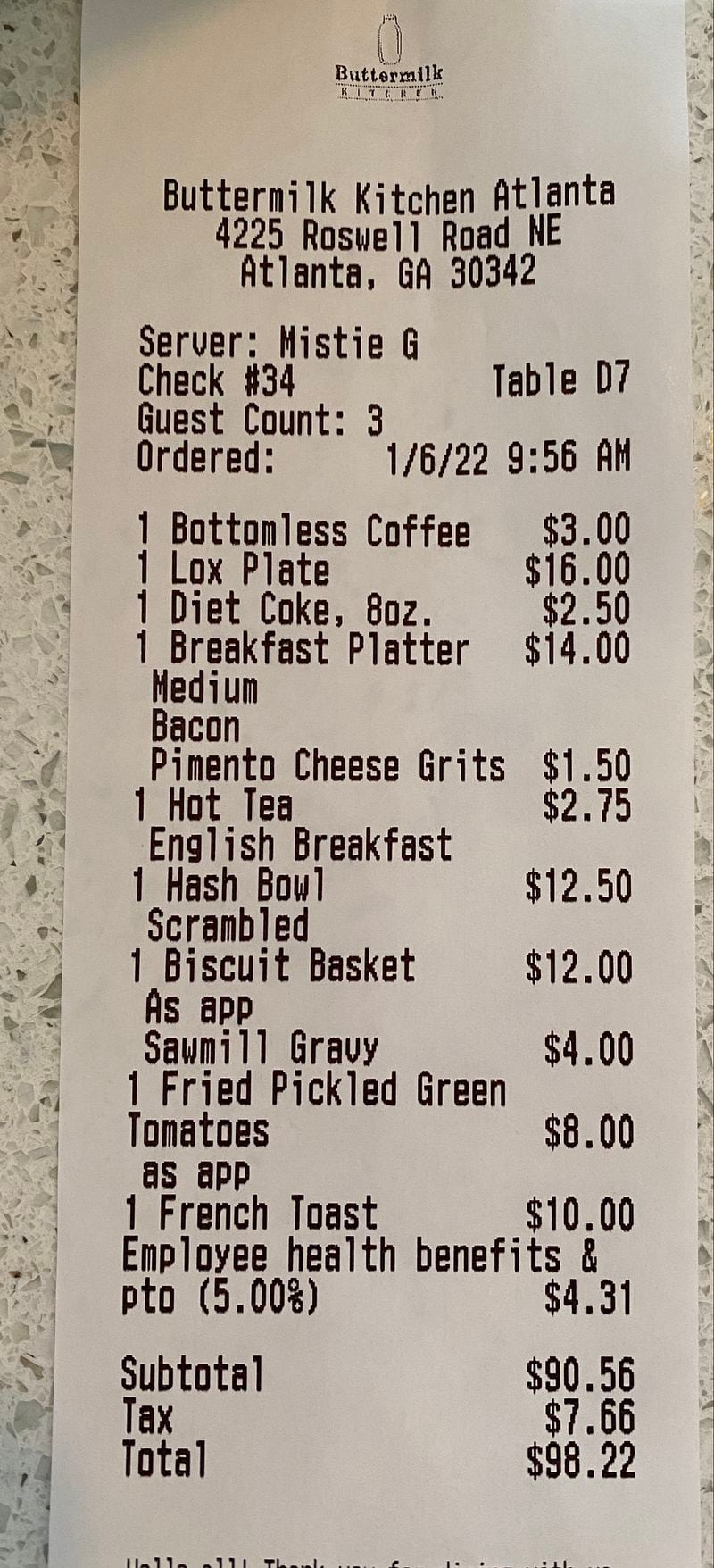

Buttermilk Kitchen owner Suzanne Vizethann has added a 5% pre-tax surcharge to all transactions to cover healthcare and sick leave. Additional charges will appear as a statement on all customer receipts.Courtesy of Sae Yamamoto Vizetan

Credit: Suzanne Vizethann

Buttermilk Kitchen owner Suzanne Vizethann has added a 5% pre-tax surcharge to all transactions to cover healthcare and sick leave. Additional charges will appear as a statement on all customer receipts.Courtesy of Sae Yamamoto Vizetan

Credit: Suzanne Vizethann

Credit: Suzanne Vizethann

Prior to the change, Vizethann could only provide health insurance to office workers. This fee allows her to provide medical care to 22 hourly employees, half of whom are registered.

“In our industry, this is totally unprecedented in a small restaurant,” she said. “It puts the spotlight on that topic. This is the way we need to start caring for people.”

Lee Lil’s, an employee of Little Tart, has her husband insured through her plans and praises her boss’s decision. “We have medical, dentistry and vision. It’s great to have them all,” she said. “For doctors, you only have to pay for yourself. You didn’t have to pay too much from your pocket. That’s great.”

Another kind of war

In the United States before World War II, employer-funded health care was not always the norm. Most Americans paid all medical expenses or had health insurance that covered only major expenses such as hospitalization. Other costs were paid directly to the provider at your own expense.

During World War II, the federal government introduced wage and price controls to employers to avoid inflation. This has led companies to offer other incentives, including health benefits, to compete for workers.

After World War II, covering people’s health care has grown worldwide. The United Kingdom, Canada, and European countries have opted for universal health insurance, funded by the government. The United States has chosen to rely on expanding the private health insurance system that employers purchase.

In the third year of the pandemic, a wave of highly contagious Omicron variants rushes in, and restaurant owners are in the same position as business owners 80 years ago, attracting employees while caring for them. I’m trying to maintain it. happiness.

“We can only pay so much to our staff,” Culvert said. “What we can do is find ways to increase value. Insurance, holding-based salary increases, achieving sales goals, access to life insurance. We offer maternity leave. Next year we offer PTO (paid leave). ). We are trying to build overall value for our staff, so it will be not only the value of wages, but also consistency, life, health and everything else. “

The food service industry is one of the countries with the highest percentage of uninsured workers in the United States. Using the data from 2013 to 2014, the 2018 survey was published. By Centers for Disease Control and Prevention It was found that 35.5% of food service workers between the ages of 18 and 64 reported not having health insurance.

Keys have always been affordable, said Karen Bremer, president of the Georgia Restaurant Association. “If it’s affordable, more employers will do it. Many employers need to consider different ways to support their employees.”

Culvert and his business partners were considering adding an additional fee at the Tycoon de Loga Club before the pandemic. After that, when the virus broke out, profits plummeted in half. “We couldn’t afford to lose any money, so we were afraid to launch it,” Culvert said. “When I realized that COVID is a way of life and never disappears, it’s like’put this in your ad application information’.”

Instead of offering health insurance plans to employees at Buckhead’s Mission and Market and Sandy Springs’ TreVele, chef partner Ian Winslade reimburses employees for up to $ 250 per month. “We have seen different plans,” he said. “They are ridiculously expensive. Health insurance is such a disastrous mess at the moment at all levels. Costs have skyrocketed and benefits have dropped dramatically. The part of joint insurance is very high. “

Winslade said affordable insurance plans are not in favor of small businesses like him, who have only 50 employees, compared to large restaurant groups with more than 100 employees.

Based in Atlanta, Fifth Group operates local restaurants such as Eco, South City Kitchen, and Alma Cocina, and currently employs 950 to 550 pre-pandemic people. We offer healthcare as part of our benefits package, but even this large restaurant group struggles to achieve its insurance objectives. “There are a lot of (insurance) companies that weren’t interested in bidding on us because we weren’t big enough,” said partner Robby Kukler.

Pandemics are exacerbating insurance costs. “It’s difficult if the usage is high in a year, like COVID, which lets team members use insurance. This tends to push up the cost of insurance,” said Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse’s four franchises at Atlanta Metro. Tish Morris, Director of Human Resources at Sizzling Steak Concepts, which runs Alpharetta’s up-on-the-roof, said.

The Unsukay Restaurant Group, which includes Binnings’ Local Three and Smyrna’s MTH Pizza, provides insurance for full-time employees (defined as those who work more than 28 hours a week). According to chef partner Chris Hall, the company has increased insurance costs by 30% to 50% over the past five years, during which time it has changed its insurance company twice. “At some point, it’s starting to reach unsustainable numbers,” Hall said. “I can’t even give you an extra charge because things are getting more and more like now, or you’ll get a $ 24 burger.”

Calvert said the extra charge for the Tycoon de Loga Club was “better than nothing”, but also complained that “the entire system was broken.” He lamented that Omicron lost $ 30,000 in total revenue in December. He urged restaurant owners in other areas to close temporarily. “Even if I have to close and I have no income, I have to pay insurance,” he said. “It’s a big challenge. Sales are declining, but insurance is the same. Once you commit, you can’t go back.”

Ask for help

Since announcing additional charges at Little Tart, O’Brien has been worried about funding Visesan’s employee health care. We will also meet with Grant Park spa owners who are interested in taking that step soon.

Vizethann answered several questions, including a question from a Florida restaurant owner. She called this process “difficult and scary” and pointed out that the restaurant business does not have much downtime or management time. “If Sarah (O’Brien) hadn’t sat down and gave an overview of the whole thing, she would probably have delayed it,” she said.

The Buttermilk Kitchen sign states that there is a 5% commission on transactions to cover employee benefits.Courtesy of Sae Yamamoto Vizetan

Credits: Handouts

The Buttermilk Kitchen sign states that there is a 5% commission on transactions to cover employee benefits.Courtesy of Sae Yamamoto Vizetan

Credits: Handouts

Credits: Handouts

Calvert has been approached by many food service industry operators, including groups that employ hundreds of people in multiple states. They were interested in the additional charges for medical expenses, but did not follow up. “If one or two do this, it will have a national impact,” he said. “It can change hundreds of lives.”

Since its inception in 2013, the non-profit Giving Kitchen has helped thousands of food service workers facing unforeseen challenges. Last year, an Atlanta-based organization served approximately 1,900 clients and provided $ 1.4 million in funding, of which more than $ 427,000 was paid to clients directly affected by COVID-19. .. Requests for assistance increased by 229% compared to 2018.

Vizethann and Calvert wonder if organizations like Giving Kitchen can play a role in helping other small businesses navigate the insurance equation.

“What if someone could help me set this up?” Calvert said. “What if Atlanta became the first city to cover the full power of restaurants?”

“People asked us before if we could be a broker, but that’s not possible from a legal or logistics standpoint,” said Brian Schroeder, executive director of Gibbing Kitchen. .. But he added that the organization is working on a toolkit for employers for operators who say they “need help to make their restaurant a better one.”

The resource will address a variety of themes, including mental health, insurance, and workplace harassment, he said. “We know that intent and heart are there. People need guidance and first steps.”

Atlanta Journal-Constitutional Healthcare Reporter Ariel Hart contributed to this article.

Sign up for the AJC Food and Dining newsletter

Read more stories like this I like the Atlanta restaurant scene on Facebook, Continue @ATLDiningNews on Twitter When Instagram @ajcdining..