For years, Meghan Neri paid $30 per package of epinephrine auto-injectors for her two adolescent children with food allergies. The price of her four packs of life-saving medicine was affordable at $120 a year.

So Neri, 42, of Stuate, Massachusetts, was shocked in 2019 when her pharmacist said each pack of auto-injectors would cost $600.

That year her out-of-pocket expense jumped to $2,400.

The price of the epinephrine injection itself had not increased. The problem was that Nellis switched to a new health insurance plan with a higher deductible to save money. Programs with higher deductibles have lower monthly payments, but families often have to pay thousands of dollars each year before many expenses, including an epi auto-injector, are covered.

Like Nellis, many families are caught off-guard by the price spike. Some have been forced to ration auto-injectors or go without them.

Dr. Purvi Parikh, an allergist and immunologist at NYU Langone Health in New York City, said: “They’re seizing the opportunity for bad outcomes.”

Parikh said families have had to shoulder more and more financial responsibilities over the past decade.

As the Affordable Care Act of 2010 expanded access to health insurance, businesses were faced with targeting more people than ever before. To make up for this, insurance companies “not only increased the cost of coverage, but pushed it onto patients in the form of high deductible plans,” he said. “It’s been like this every year for at least the last seven to 10 years.”

An analysis by the KFF, also known as the Kaiser Family Foundation, found that in 2009, 17% of workers had health insurance with an annual deductible of at least $1,000. By 2021 he will be 50%.

KFF executive vice president Larry Levitt said:

Some family plans have deductibles well over $3,000.

“It means that even if you have insurance, you may not actually be protected against devastating medical costs,” Levitt said.

Prescriptions that used to cost around $30 (basic out-of-pocket) are now full price and can jump to hundreds of dollars.

Some medicines, such as those that control high blood pressure, are covered even before the deductible is met. But epinephrine auto-injectors, which provide a shot of adrenaline and are the only emergency medication available for life-threatening allergic reactions, usually don’t.

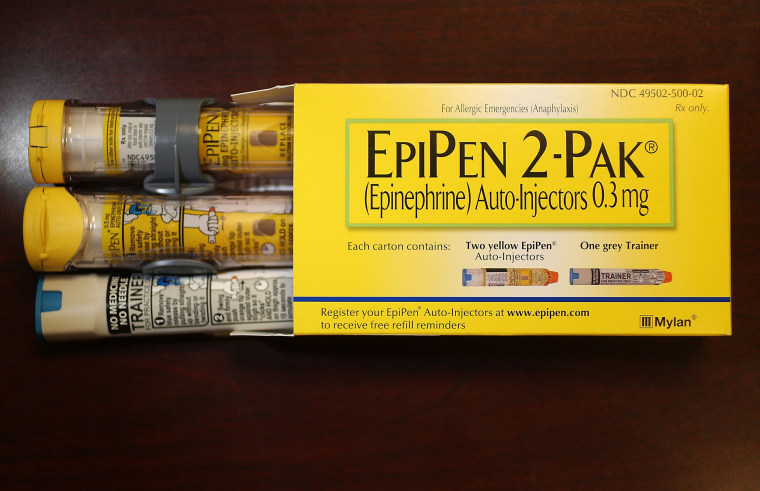

Few prescription drugs or medical devices represent uncontrollable medical costs higher than the EpiPen.

From 2008 to 2016, the Mylan pharmaceutical company increased the price of its auto-injectors by more than 400%, leading to public outrage and congressional scrutiny.

We hoped other epinephrine delivery products, such as Adrenaclick and Auvi-Q, would soon come along with generics and create a price point that more people could afford.

Dr. Kao-Ping Chua, assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Michigan School of Medicine and the Susan B. Meister Center for Child Health Assessment and Research, said: Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Side Effects: Details of US Drug Costs

But after switching to a plan with a higher deductible, some patients, like Nellis, found themselves charged almost full price for their epinephrine autoinjector.

Neri’s daughter Shea, 14, is allergic to milk, and her son Thomas, 12, is allergic to cow’s milk, peanuts and tree nuts. The little Fanny she always wears never leaves the house without a device in her pack in case she gets infected.

“You want it to be wasted medicine and wasted energy,” Neri said.

Injectors last an average of only one year. The Neri family must buy her four auto-injector packs for their two children each year to keep them at home and at school. Shea and Thomas each had to use emergency epinephrine injections.

When the pharmacist told Neri the new price for the refill, she was devastated and didn’t pay the $2,400 that day.

“I was a little embarrassed to say ‘I can’t do it now,'” she said.

The deductible is intended to discourage improper use of medical care and abuse of prescription drugs, Levitt said. But epinephrine auto-injectors save people’s lives.

“No one is using them inappropriately,” he said.

Indeed, Neri said an auto-injector is a necessary tool to protect her child.

People don’t expect to pay this much when they have health insurance.

Pediatrician Dr. Kao-Ping Chua, University of Michigan School of Medicine

“This is not a choice. You can’t choose anything about this,” she said.

Epinephrine is the first line of defense when a person has a severe allergic reaction called anaphylaxis. When this happens, blood pressure drops sharply. The airways narrow and breathing becomes difficult. A shot of epinephrine, or adrenaline, can reverse what would otherwise be fatal.

“For high-value, life-saving drugs, out-of-pocket costs should be zero,” said Chua of the University of Michigan.

Chua has spent years researching how much families pay for emergency epinephrine. He led a study published in his July that found one in 13 of his patients was paying more than $200 a year for an epinephrine auto-injector.

Mostly children, not only because allergies are more common in children than adults, but also because of the need to store multiple auto-injectors during home, school, and after-school activities.

In Chua’s study, the majority (62.5%) of families paying more than $200 a year had health insurance with high deductibles.

“I see this primarily as a benefit design issue,” said Chua. “People don’t expect to pay this much because they assume that if they have health insurance, their medication will be covered by their insurance.”

Patients may question high fees

“Whether medical services or medicines are exempt from the deductible is usually up to the insurance company, and in the case of workplace health insurance, the employer,” said Levitt.

Health insurance companies can waive epinephrine auto-injectors from high deductibles. UnitedHealthcare has announced that starting next year, some plans will no longer have epinephrine copayments or other copayments.

It’s the only major health insurer to cover epinephrine so far, but “we’re seeing more and more insurers waiving out-of-pocket costs for life-saving drugs,” Levitt said.

Chua said limiting the cost of other life-saving drugs, such as insulin for diabetes and naloxone, which controls opioid overdoses, is also good public policy.

However, the AHIP (formerly known as the American Health Insurance Program), a group representing such companies, says the pharmaceutical companies are to blame.

“We encourage big pharmaceutical companies to end their price gouging tactics and lower prices for unruly patients,” the group said in a statement to NBC News. “Patients need life-saving drugs, so no drug options mean there is no incentive for big pharma to agree to lower prices.”

Ultimately, it’s up to patients to navigate their medical plans and struggle to find a way to pay for expensive medications.

“The most important thing to know is if you have to pay a drug deductible before insurance applies,” Chua said.

After spending the day at the pharmacy, Neri delved into the family’s health insurance plan and contacted her primary care physician to discuss other options.

They switched to another brand of emergency epinephrine and now pay $25 per pack.

“We were going to use what we needed to keep them safe,” Neri said. “But it helps to have enough information to make an informed decision and not feel like you’re wasting money unnecessarily.”

Levitt said patients should feel empowered to question high fees.

“It’s a lot of work,” says Levitt. Fight healthcare providers, fight insurance companies. “

“No, it makes little sense with health insurance,” he said. “You can often win.”

follow NBC Health upon twitter & Facebook.