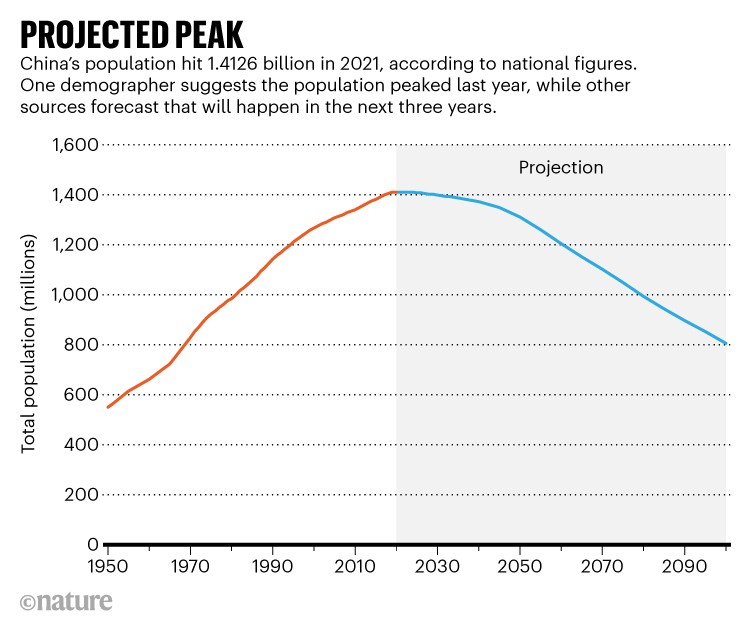

When will China’s population, the world’s largest, peak? The point, demographers say, is that it’s fast approaching. The country’s health department announced this month that the population will peak and begin to decline over the next three years. Others think it could happen sooner.

“The tipping point is just around the corner,” says Yong Cai, a demographer at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

After years of declining birth rates, the National Health Commission said in an article published online in early August that China’s population growth would slow significantly and begin to decline between 2023 and 2025. I wrote. journal, social science journal1Wei Chen, a demographer at Renmin University in Beijing, has concluded that China’s population may already have peaked in 2021, based on census data released in 2020. (See “Predicted Peaks”).

The Chinese government has made great efforts to increase the birth rate over the past decade. This includes overturning decades of population control policies in the country. Demographers say changing attitudes toward parenting among younger generations are also contributing to slowing growth. This trend is likely to continue, they say, and an aging population will pose a major challenge for the country.

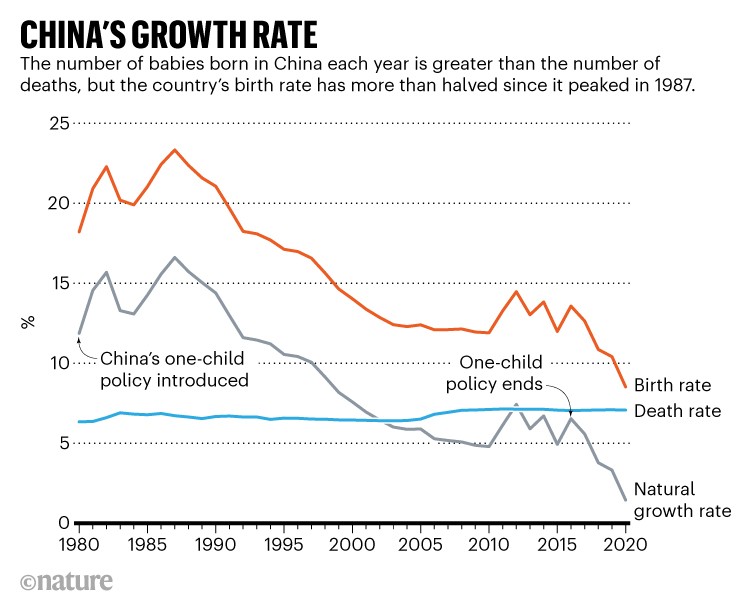

Last year, China’s total population grew by just 480,000 to over 1.41 billion, with a natural increase rate (the difference between births and deaths) approaching zero. The country’s fertility rate fell for the fifth year in a row, to 7.5 per 1,000 people, and the number of babies born in 2021 will remain at her 10 million, the lowest since 1949.

change in attitude

In the 1960s, after the Great Famine in China, there was a big baby boom. To curb rapid population growth, the government initiated his one-child policy in 1980, restricting most families to having only one girlfriend. With this strategy, the country’s population growth rate fell from 2.5% in 1970 to 0.7% in 2000. However, this policy did not end until 2016 (see China’s growth rate). Many demographers, including his Jianxin Li of Peking University in Beijing, think the end of the policy is too late to reverse the country’s plummeting birth rate. In 1997, Lee predicted that China’s population could peak in 2024 if population control policies continued.

Researchers say China’s fertility rate has continued to decline even after the one-child policy ended, due to changing attitudes toward marriage and childbearing and young people delaying marriage and childbearing. According to her Jian Song, a demographer at Renmin University of China in Beijing, more women are getting higher education and gaining paid jobs, so women are starting families later in life than previous generations. It is said that they are starting to have it.

According to the data, the average age of first marriage for men and women in 2020 was about 29 and 28, respectively. The first marriage in 2010 was with a woman at her 24 and a man at her 26. Song added that in China, most people choose to have children after marriage, and having children later in life means that women tend to have fewer children.

Younger generations tend to start marrying and having children more cautiously when they are financially ready, according to Yang Shen, a sociologist at Shanghai Jiao Tong University in China. “Most young people today still want to have families, but the economic pressures of housing and childcare can seriously discourage them from doing so,” says Shen.

A study found that 45% fewer babies were born in the last two months of 2020 compared to the same period in 2015. This suggests that her COVID-19 epidemic, which hit China in early 2020, has influenced the couple’s decisions about whether to have children.

Aging society

China’s “fertility tsunami” is exacerbated by fewer women entering childbearing age, says Tsai. Far fewer babies were born in the 1990s than in the 1980s. The women of that generation are now of childbearing age, but will collectively have fewer children than previous generations. “Demographically, there is strong negative momentum,” Kai says.

At the same time, baby boomers born in the 1960s are approaching their 60s. “In the next 10 to 20 years, China will have a rapidly growing elderly population, which will be a major challenge for society,” Song said. Currently, more than 18% of him in China’s population are over the age of 60. That proportion is expected to reach 300 million, he said, by 2050 he will increase by one-third.

Population aging is a family expense and a government financial problem. Tsai’s team predicts that public spending on health care will double between 2015 and 2050 due to an aging population. “To address the problem of an aging population, we need to start preparing the resources needed to care for the elderly now,” Song said.